Case Closed: DNA Finally Proves Jack the Ripper's True Identity

The Disturbed Barber, The Forgotten Women, and the DNA That Finally Solved History's Most Infamous Murder Case

For 137 years, the name "Jack the Ripper" has haunted the dark corners of true crime history. The faceless killer who terrorized London's Whitechapel district in 1888 became a phantom, spawning countless theories, books, and Hollywood adaptations. But behind the sensational headlines and amateur sleuths lay a darker truth: five women whose lives, dreams, and struggles were overshadowed by the mystique of their killer.

Today, as DNA evidence points to Aaron Kosminski, a 23-year-old Polish barber, as the man behind the murders, it's time to tell the full story - not just of how the case was solved, but of the lives that were lost and the society that failed them.

The Women Who Were More Than Victims

Mary Ann "Polly" Nichols: The Proud Mother

Born Mary Ann Walker in August 1845, Polly Nichols embodied the precarious nature of Victorian working-class life. Her story begins not in the dark alley where she died, but in a modest home on Dawes Street. She married William Nichols in 1864, bore five children, and maintained a respectable working-class life until her marriage crumbled - not due to her alleged "drunken habits" as previously reported, but because of William's affair with their children's nurse.

Polly was literate, well-spoken, and proud of her cleanliness even in poverty. She worked as a domestic servant in wealthy homes, struggling to maintain her independence. Her father offered her shelter, which she sometimes accepted, but her fierce pride often led her back to the streets. The night before her death, she had earned her lodging money but spent it on alcohol - a fatal decision that forced her onto Whitechapel's deadly streets. Her last words captured her eternal optimism: "I'll soon get my doss money. See what a jolly bonnet I've got now."

Annie Chapman: The Flower Maker

Annie Chapman's descent from respectability to poverty exemplifies how quickly fortune could turn in Victorian London. Born Annie Eliza Smith in 1841, she grew up in Knightsbridge, daughter of a soldier-turned-valet. Her marriage to John Chapman, a coachman, gave her three children and a stable life until tragedy struck. Their firstborn, Emily Ruth, was born disabled and institutionalized. Their son John died of meningitis at twelve. These losses drove both parents to drink.

After her husband's death in 1886, Annie supported herself by selling crochet work, flowers, and matches. Despite suffering from tuberculosis, she was known for her skill at making artificial flowers from paper and her generosity - sharing what little she had with others at Crossingham's lodging house. Her friends remembered her saying, "I'm not going to live long," but she never stopped trying to make beauty in her harsh world.

Elizabeth Stride: The Swedish Survivor

Elizabeth Stride's journey began far from London's East End. Born Elisabeth Gustafsdotter in Torslanda, Sweden, in 1843, she came from a farming family and sailed to London in 1866 seeking a better life. She married John Stride in 1869, and together they ran a coffee shop in Poplar until its failure and his death in 1884.

Known as "Long Liz," she taught herself English, learned to sew, and participated in the Match Girls' Strike of 1888, showing her solidarity with other working women. Though she invented elaborate stories about losing family in the Princess Alice disaster, friends knew her as cheerful and hardworking. She lived with Michael Kidney, a waterside laborer, cleaning houses and showing kindness to neighborhood children.

Catherine Eddowes: The Storyteller

Perhaps the most vibrant personality among the victims, Catherine Eddowes was born in Wolverhampton in 1842 to an Irish Catholic family. Well-educated and highly literate, she made her living as a "hawker" with her long-term partner Thomas Conway, writing and selling ballads on the streets. Her nephew described her as "a very jolly woman" who "used to sing songs and be pleasant with everybody."

Catherine's wit and storytelling abilities made her a popular figure in local pubs. Even on the night of her death, after being released from police custody for public drunkenness, she maintained her humor, bidding the officers goodbye with a playful "Good night, old cock."

Mary Jane Kelly: The Mystery

The final canonical victim remains the most enigmatic. Mary Jane Kelly, believed to be born in Limerick around 1863, wove different tales of her past - some claiming Welsh nobility, others suggesting work in high-class West End brothels. What's certain is that by 1884, she lived in Whitechapel's Miller's Court, known as "Fair Emma" for her striking red hair.

Living with fish porter Joseph Barnett, Kelly was known for her kindness, often sheltering homeless women in her small room. Fluent in Welsh, she sometimes worked as a translator for the local Welsh population. At 25, she was the youngest victim, described as strikingly beautiful with blue eyes and a fair complexion.

The World They Lived In

Victorian London's East End was a place of stark contrasts. While the British Empire reached its zenith, its capital's poorest district struggled with overcrowding, disease, and desperate poverty. The influx of immigrants, including Jews fleeing Russian pogroms, created tensions in an already strained community.

For women, options were particularly limited. A single misfortune - the death of a spouse, loss of employment, or illness - could begin an irreversible slide into destitution. The workhouse loomed as a dreaded last resort, while the streets offered a dangerous but more independent alternative.

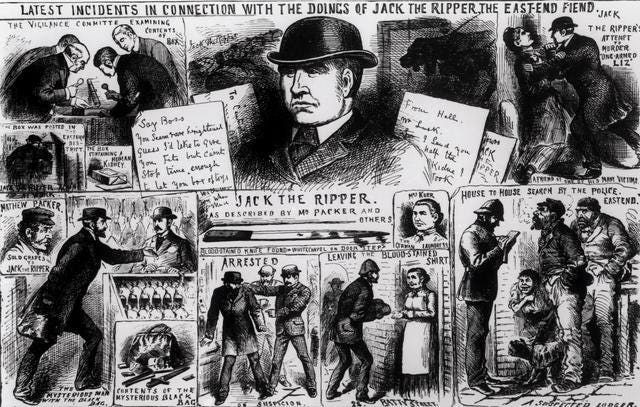

The Investigation: From Victorian London to Modern DNA

The initial investigation was hampered by jurisdictional issues between the Metropolitan Police and City of London Police, primitive forensic techniques, and social tensions. Anti-Semitic prejudices complicated matters, particularly when Jewish witnesses proved reluctant to cooperate with authorities they didn't trust.

Contemporary police documents, particularly notes by Chief Inspector Donald Swanson and Assistant Commissioner Sir Robert Anderson, consistently named Aaron Kosminski as their prime suspect. They had a witness - another Jewish man - who identified Kosminski but refused to testify against a fellow Jew, leaving Victorian-era police powerless to act.

Aaron Kosminski: The Man Behind the Myth

Born in Kłodawa, Poland, in 1865, Kosminski fled to London with his family escaping anti-Jewish pogroms. Working as a barber in Whitechapel, he lived with his siblings while showing increasing signs of mental illness. Hospital records describe a young man tormented by auditory hallucinations and paranoid delusions, refusing food from others and living on bread and pickles.

His deteriorating mental condition, combined with a documented hatred of women, drew police attention. By 1890, his family had him committed. He spent the remainder of his life in asylums, dying in 1919 of gangrene.

The DNA Evidence

The breakthrough came through a shawl found near Catherine Eddowes' body. While its chain of custody raised questions, advanced forensic techniques matched genetic material on the shawl to both Eddowes' descendants and Kosminski's family line. This evidence, combined with contemporary police suspicions, presents the strongest case yet for Kosminski's guilt.

Legacy and Lessons

The Ripper murders catalyzed changes in policing, including the use of crime scene photography and timeline analysis. They exposed the harsh realities of Victorian poverty and the vulnerable position of women in that society. The case's impact on London's Jewish community highlighted the dangerous consequences of prejudice and fear.

But perhaps the most important legacy should be remembering the women themselves: Polly Nichols, who never lost her pride; Annie Chapman, who created beauty with paper flowers; Elizabeth Stride, who fought for workers' rights; Catherine Eddowes, who entertained with her songs and stories; and Mary Jane Kelly, who shared what little she had with those even less fortunate.

Closing the Case, Opening Understanding

As we finally put a face to Jack the Ripper, we must remember that solving this mystery doesn't end the story - it merely shifts our focus to where it should have been all along. These women were not just victims of a killer; they were victims of a society that provided little support or protection for women in crisis.

Their lives remind us that behind every victim of violence is a full and complex human being - someone who loved, struggled, dreamed, and deserved far better than their place in history as mere footnotes to a killer's story.

In closing this chapter of criminal history, we should remember not the shadowy figure who killed them, but the vibrant women who lived. Their stories continue to resonate, teaching us about resilience in the face of hardship, the importance of social support systems, and the human cost of society's failures.

The true legacy of the Ripper case isn't the identity of the killer - it's the lesson that every victim has a story worth telling, every life has value, and every society bears responsibility for protecting its most vulnerable members.

Not a fan of what I call,”murder and mayhem, I really enjoyed your work. Victim shaming is real and as old as mankind. Because women have the potential to bear children, they are held to a different standard. These victims have always been throwaways in the story; drunken prostitutes who got what they deserved. Their murderer has been mythologized, deemed so cunning and clever the only explanation was he was of royal birth. The hard truths are societal values and inhumanity. Bravo on your fresh perspective.

I love seeing the Ripper’s victims given the humanity they deserve, but I still say we will not be able to definitively ever say “this is who Jack the Ripper was.” Is it more than likely, with the evidence we do have, knowing he was a major suspect, that it was Kominski? Absolutely. However, what we have is A shawl that we believe to have been Eddowes that had both their (families) DNA on it. A shawl that wasn’t handled as carefully as we would handle evidence now. Matter of fact it ended up in private hands immediately as it was a cop who snagged it. We have no idea of what could have happened to that shawl, no idea when that DNA ended up on that shawl, or even if there is a legitimate reason for it having been there as we don’t know for sure if she was or was not, a prostitute. If she was, that semen DNA (which is what they found) could have been there legitimately and from who knows when, and not because Kominski killed her.

We have a single piece of evidence that is damning, but we can prove nothing around it, we can’t even prove it was hers.

So while it is more than likely Kominski was Jack the Ripper, what we have as proof would never be able to condemn a man today as it was never handled correctly. Maybe had the shawl been taken into evidence and we dug it up years later hidden away in the police station… but it wasn’t. We have a shawl a we’ve been told was taken from Eddowes, that was in private hands, that anything could have happened to.

Can you imagine if we had that as evidence now? Something stolen from the scene of the crime, not handled carefully, and then privately tested. Privately tested, and can only prove that DNA from the same family was on it? Not like we have known samples from each person and can perfectly match it to having belonged to Eddowes and Kominski.

The shawl evidence does not 100% prove who the Ripper was, it can’t, it can only prove its highly likely that Kominski was the killer. It’s almost the best evidence possible in this situation, and yet it was handled so badly we can’t rely on it.

It’s a shame, but unless we can prove the shawl was absolutely Eddowes, that there was no legitimate reason for his dna to be on it, and that no one did anything to that shawl while it was in private hands… we can’t rely on it as proof.